Functional Programming

This post is not intended to deep dive into all functional concepts. The idea is to keep it concise and small enough to give a fair understanding of some functional principles.

Imperative x Functional

The imperative paradigm solves problems through a sequence of statements that modify the state to reach a specific goal. The functional approach treats everything as functions (values), minimizing the “moving parts” through immutability, avoiding state management when possible and describing programs as expressions and transformations.

Side Effects

A function or expression is said to have a side effect if it modifies some state outside its scope. Side effects are not evil as you need it to persist data and display information. An application without any side effects is usually useless. The idea is to maintain side effects under control in the system parts that makes sense to have it.

Pure Functions

A function is pure if it has no side effects, in other terms always perform the same computation, resulting in the same output for given a set of inputs, ex:

F(x) = 1 / x

We can predict the output given an input, no matter how many times the above expression is executed the result will always be the same. Pure functions are easier to be tested and leverage a better understanding of the code’s functionality, as it tends to do more specific tasks and be smaller.

Immutability

Immutability is a fundamental concept of functional programming. The idea is to avoid state changes to reduce complexity as you wouldn’t have to care about state management. For example, a variable/object can be changed at any given time or passed by reference to methods making it hard to track when and where things are being computed. One of the reasons that OOP languages mechanisms like encapsulation, scoping and visibility exists is to make state changes under control. Michael Feathers made a fairly citation regarding it.

OO makes code understandable by encapsulating moving parts. FP makes code understandable by minimizing moving parts.

-Michael Feathers

Immutability really shines when we talk about concurrency, if nothing is shared between threads, then you don’t have to worry about locking mechanisms, avoiding issues with deadlocks, race conditions and thread starvation.

First-class functions

First-class functions are another core principle needed in any functional language. In fact, it is just functions that can either accept another function as an argument or return a function. First-class functions are always treated as values.

(map inc '(1 2 3)) ;=> (2 3 4)

In the example, we pass the inc function to the map function, that will iterate the list and apply the inc to each element. First-class functions are a necessary abstraction for code reusability when talking about functional paradigm.

Closure

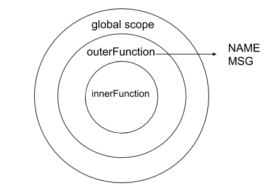

A closure is a function that carries a binding to the variables referenced within it, a technique for lexically scoped name binding with first-class functions.

(defn hello [name]

(let [msg (str "hello " name)]

(fn [] msg)))

((hello "foo")) ;=> "hello foo"

The hello function returns an anonymous function that continues having access to msg even after hello have resolved, following at some point the principle of least privilege.

Currying & Partial

Currying gives you the ability to manipulate the number of arguments to functions, binding arguments at first moment that returns a new view of this function with preset arguments.

; ps: sum operator is a function

(def incrementer (partial + 1))

(incrementer 3) ; => 4

In the above example, the generic sum function was used to create a new one, an increment function. Partial is slightly different from currying, besides the similar result, currying transforms a function with multiple arguments into a chain of single-argument functions and partial supply some arguments to a function, getting back a new one that takes the rest of the arguments. Currying is usually used to overcome problems that OOP design patterns like factory and template are intended to solve.

Function Composition

Function Composition is the process to combine two or more functions to produce a new one.

In the following example, If Y ⊆ X, then f: X→Y may compose with itself:

(f∘f)(x) = f(f(x))

(f∘f∘f)(x) = f(f(f(x)))

Or if f: X → X and g: X → X you can combine than in any order, creating a chain of transformations like:

(f∘g)(x) = f(g(x))

(g∘f)(x) = g(f(x))

(f∘f∘g∘g) = f(f(g(g(x)))

To a function be composable it should accept one argument and return one value. One thing to note is that currying has a vital role to achieve composable functions in the real world. The next example extends the currying example to fit in a composable solution, showing that two single functions can be used in several different ways to solve different problems.

(def incrementer (partial + 1))

(def double (partial * 2))

(def inc-and-double (comp double incrementer))

(def double-and-inc (comp incrementer double))

(inc-and-double 1) ; => 4

(double-and-inc 1) ; => 3

Composable systems have less implicit behavior but lead to more reusability, providing a more granular code that can be combined in different ways to solve different problems.

Recursion

Functional programming languages usually do not offer looping statements. Instead, functional programmers rely on recursion. Recursion is the act of a function allowing to call itself, many times recursion leads to a more straightforward solution as the state management is delegated to the runtime minimizing the “moving parts” of your application.

(defn factorial [n]

(if (#{0 1} n)

1

(-> n bigint dec factorial (* n))))

; => 4 * (factorial 3)

; => 4 * 3 * (factorial 2)

; => 4 * 3 * 2 * (factorial 1)

; => 4 * 3 * 2 * 1

(factorial 4) ; => 24

; oh-no

(factorial 10000) ; => java.lang.StackOverflowError

Recursion can store intermediate results on the stack, that can cause a stack overflow. Because of this “limitation”, some languages implement a tail-call optimization, that is when the recursive call is the last call in the function, and the language runtime replaces the results on the stack rather than create new memory frames.

(defn factorial [n]

(loop [n n acc 1N]

(if (#{0 1} n)

acc

(recur (dec n) (* acc n)))))

(factorial 10000) ; => A really big number

In Clojure it is explicit because you need to use loop/recur, but for many other languages, the only thing that is required is to make sure that the function call is on tail position.

Processing data

Once we have a collection of values, we need to be able to filter and transform it into new forms to satisfy our application needs. Imperative languages process collections over loops and tend to force you to complete the tasks within a single loop, in functional languages we can leverage the power of first-class functions and use map, filter and reduce in our favor to operate over collections, that usually makes things easier to read and maintain.

(def persons [{:fname "foo" :lname "bar" :age 20}

{:fname "lorem" :lname "ipsum" :age 88}

{:fname "bob" :lname "jr" :age 15}])

; return a list with full name of persons older than 18

(->> persons

(filter #(-> % :age (> 18)))

(map #(clojure.string/join " " [(:fname %) (:lname %)])))

; sum the age of persons that are younger than 25

(->> persons

(filter #(-> % :age (< 25)))

(map :age)

(reduce +))

Final considerations

To shift from an Imperative language to a Functional language you need not only to know and understand some core concepts but also to change the way of thinking, that in my opinion is the hardest part. Also, modern languages support many of the concepts talked in this text, generally speaking, you don’t need to be in a functional language to write functional code.

Til next time,

Felipe Beline Baravieira

at 15:27